Research presented at the 2018 CHI Conference by Michael Fernandes (BS '17) aims to help people make better decisions by communicating uncertainty in predictions.

Michael Fernandes (BS, '17) presenting his research at the 2018 CHI Conference, where it received a Best Paper Honorable Mention award.

Michael Fernandes (BS, '17) presenting his research at the 2018 CHI Conference, where it received a Best Paper Honorable Mention award.

Today’s smartphones give people a way to quickly use predicted information to make everyday decisions, from deciding what to wear for the day based on weather prediction, to deciding when to buy an airplane ticket based on price predictions. But with every prediction there is a degree of uncertainty that is not communicated to the decision-maker.

A team of researchers at UW and the University of Michigan want to help people understand just how much uncertainty is within the predictions they see on their phone, to help people make the best decision possible.

Michael Fernandes (BS ‘17) is the lead author on a paper about this research, which received a Best Paper Honorable Mention award at the 2018 CHI conference on human-computer interaction. "Previous research shows that more and more people are making these quick decisions with predictive apps,” Fernandes said. “We want to figure out the most effective way to communicate uncertainty to the average person, and not just to those who are are literate in statistics.”

To study this, Fernandes and the research team conducted a controlled experiment to study how people make decisions about when to catch their bus. The team used a modified version of OneBusAway, a real-time bus arrival time application widely used in Seattle. Fernandes used the user-centered design process to design and rebuild OneBusAway, modified to incorporate uncertainty information.

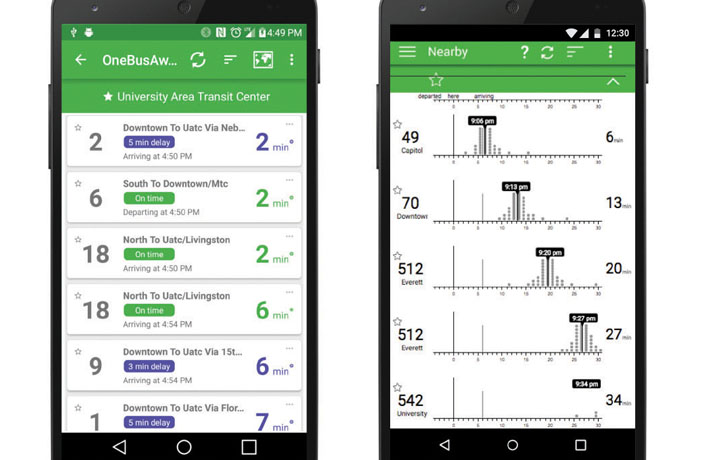

The phone on the left shows the current OneBusAway app used in Seattle as of September 2017, displaying predicted departures for an individual bus stop. The interface on the right is the rebuild created by the researchers, using quantile dotplots to display uncertainty.

The phone on the left shows the current OneBusAway app used in Seattle as of September 2017, displaying predicted departures for an individual bus stop. The interface on the right is the rebuild created by the researchers, using quantile dotplots to display uncertainty.

The researchers asked participants to complete multiple tasks, each representing a single decision about when to arrive at the bus stop given a realistic scenario, and participants used one of ten different “uncertainty displays” to make their decision about when to catch the bus. The researchers found that two types of displays, quantile dotplots and cumulative distribution plots, both led people to make better decisions.

“This work is exciting to me when I think about how it can be scaled,” Fernandes said. “More than just helping one person making a decision, when you think about how technology can help everyone make better decisions, you can help make a lot of lives easier.”

Co-authors on this paper are Sean Munson, associate professor in HCDE; Logan Walls, UW iSchool alumnus; Jessica Hullman, assistant professor in the UW iSchool; and Matthew Kay, assistant professor at the University of Michigan.