Leah Pistorius

April 9, 2021

Photo by Mark Stone, University of Washington

In HCDE's course on designing trustworthy systems, a team of master's students explored a multicultural education strategy for combating misinformation.

The prevalence of misinformation, disinformation, and strategic manipulation in online environments has become so pervasive that in 2020 the World Health Organization coined the term infodemic to describe the current crisis.

Kate Starbird, an associate professor in the Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering, has been researching how rumors spread online during crisis events for more than a decade. In recent years, Starbird's research has focused on the online spread of misinformation and disinformation. In 2019, Starbird joined colleagues from the Information School and the School of Law to co-found the Center for an Informed Public, with a mission to resist strategic misinformation, promote an informed society, and strengthen democratic discourse.

HCDE master's students Ryan Alli, Honson Ling, and Patriya Wiesmann focused their final project on alleviating pain within immigrant families caused by conversations on misinformation.

HCDE master's students Ryan Alli, Honson Ling, and Patriya Wiesmann focused their final project on alleviating pain within immigrant families caused by conversations on misinformation.

In Autumn 2020, Starbird provided HCDE students hands-on experience in this emerging space by leading a new course on trustworthy systems design. Dr. Tom Wilson, a recent PhD graduate from HCDE who researches the dynamics and structure of disinformation, co-designed and taught the course with Starbird.

"Taking this course at the height of the US election, and during the pandemic, we were able to explore this problem as it was right in front of us," said Patriya Wiesmann, an HCDE master's student in the course. "Kate and Tom brought in guest speakers from social media platforms to speak about their evolving policies on misinformation, as well as PhD students in HCDE who shared their deep knowledge in this field. It was incredibly valuable to hear from these experts, and at the same time eye-opening to realize that even the experts don't have all of the answers right now."

Every week, the students read new material to gain a holistic overview of the history and current reality of misinformation and disinformation worldwide, and discussed what these phenomena mean for online systems today and in the future.

"The class was really an exploration of a problem space," said master's student Ryan Alli. "It wasn't like, 'today we're learning about this or that,' but rather let's come together as designers and thinkers, folks in tech, and explore what is here. What opportunities do we see, understanding the context is that online systems are vulnerable to false information spreading."

According to Honson Ling, an HCDE master's student in the course, conversations about these dynamic problems cannot happen in a vacuum or within one discipline. "The composition of class helped us talk about these issues really broadly," Ling said. "In class with us were graduate students from the Information School, the Master's in Human-Computer Interaction and Design program, and the School of Law. That helped bring in insights from people who specialize in big data, or ethics in data privacy, legal policies, UX, or product design."

Support to get on the same level

For a group project in the class, Wiesmann, Alli, and Ling teamed up on a project close to their hearts — supporting immigrant families in identifying false and misleading information.

"We wanted to focus on micro-interactions," Ling said. "You often hear about viral misinformation in the widespread setting, where a policy change puts a blanket 'fix' on everything. But there is an area that's not well explored — and it is what our discipline can bring to this space — that is looking at the experience within the human-to-human interaction."

Ling, Alli, and Wiesmann are all children of immigrants. Through their early group discussions, they discovered that they shared similar experiences talking about misinformation with their families. "We started talking to friends and family members about the problem to see if it actually was a problem, and everyone was corroborating our experiences — almost identical stories across the board," said Alli.

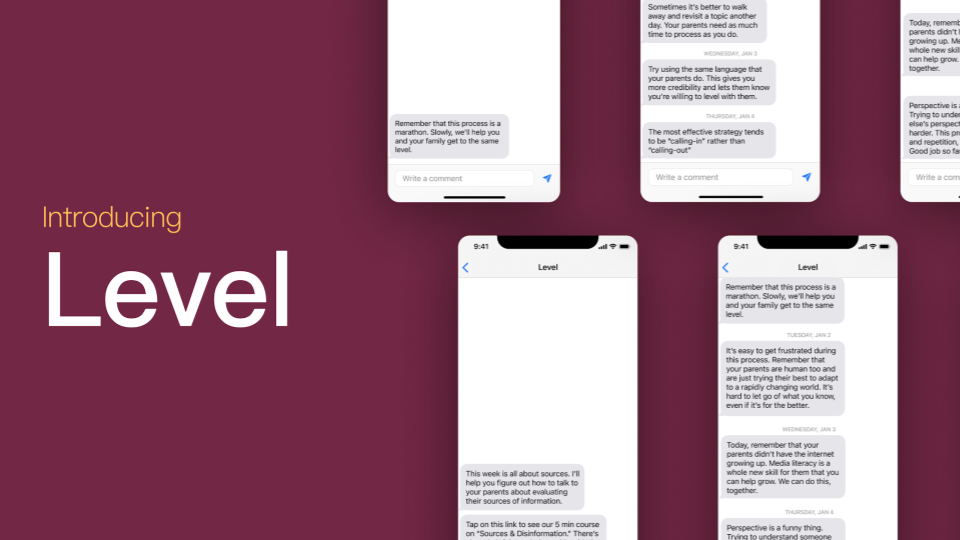

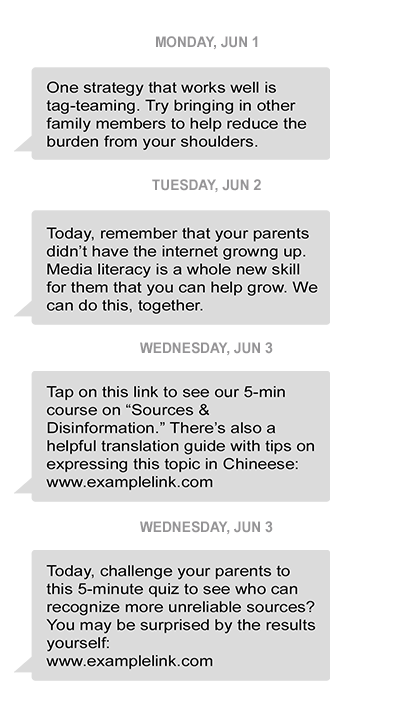

Both a strategy and a system, Level is a texting service tailored to an individual's identity and situation. Level checks in with children of immigrant parents to share tactics for communicating about disinformation. Interspersed with the strategies and tips, Level supports mental health by sharing messages that help the children empathize with their parents and foster healing dialogue.

Both a strategy and a system, Level is a texting service tailored to an individual's identity and situation. Level checks in with children of immigrant parents to share tactics for communicating about disinformation. Interspersed with the strategies and tips, Level supports mental health by sharing messages that help the children empathize with their parents and foster healing dialogue.

"We were seeing how different immigrant communities were being targeted by disinformation campaigns," said Wiesmann. "We were really surprised by how false information was localized and targeted so specifically at these communities to try to shift their thoughts."

The team interviewed children of immigrant parents, and a second-generation immigrant parent, to gather an understanding of the experience of having these conversations across generations.

Through the interviews, the students uncovered themes of cultural and linguistic barriers. They found that cultural and family dynamics play a role in how children can affect their parent's existing beliefs, and that those in older immigrant social circles often rely on a culturally homogenous community for information. They also discovered how these conversations can be emotionally taxing for both the child and the parent.

The team designed Level, a texting service to help young people in immigrant families talk to their parents and grandparents to help them identify online misinformation. Designed to communicate directly with the child, Level provides educational content in the form of a video or a quiz, and delivers a conversation starter to help the child start the dialogue with their parent. Because these conversations can be emotional, Level supports a healing process by delivering mental health check-ins after difficult conversations.

The team hopes to continue exploring this research area, expanding it to other cultures and languages, and exploring what the parent-side of a texting service could look like.

"After taking this class, my eyes are open to how minute changes to a piece of fact can be taken to create rippling waves of information — it's a butterfly effect," Alli said. "If someone with a strategic objective takes a piece of information and spins it in such a way, entire families and communities can be convinced to do something they might not have done otherwise. In Kate's class, we learned the solution is not going to be as simple as slapping up a fact-checking algorithm and calling it a day. It's our job to figure out how to build in the context of these problems. In HCDE, we have been pushed to get face-to-face with people, learn about them and what they need, and go out and build something with them."