Zakiya Hanafi on Translating Works of Philosophy

“This is a powerful and paradigm-shifting aesthetics of society, by a great philosophical talent.”

~Simon Critchley, author of Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us

It’s the second week of Women in Translation Month! This week’s #WITMONTH feature comes to us from Italy. In Social Appearances: A Philosophy of Display and Prestige, Barbara Carnevali offers a philosophical examination of the roles played by appearances in social life. While Western metaphysics and morals have predominantly disdained appearances and expelled them from their domain, Carnevali invites us to look at society, ancient to contemporary, as an aesthetic phenomenon. In today’s post, the book’s translator, Zakiya Hanafi, shares the observations that inspired her to become a translator and discusses why this particular translation is so important today. Read on to learn how translating Social Appearances influenced her perception of reality, and remember to enter this month’s drawing for a chance to win a copy of the book!

• • • • • •

Credit: Williams-Sonoma catalog image of Imperia Pasta Machine.

I used to think that reality was a stuff that got segmented into different parts depending on the language you spoke. Kind of like a pasta machine, I’d tell my students. You know, you feed a mass of amorphous dough into one end of the roller and what comes out the other end depends on the filter you put on it: spaghetti, ravioli, fettucini, capellini . . .

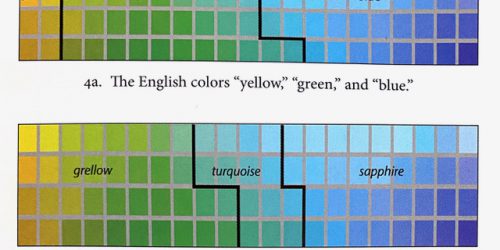

The image isn’t entirely frivolous. There’s loads of recent research on color perception showing that the palette of colors available to our cognition depends on the number of words in our native language: our culture literally segments the infinite number of frequencies that arrive at our eyes into just a few or a multitude of hues, depending, for example, on whether blue and green are differentiated, as in English, or, whether, as in Japanese and Chinese, they’re called by the same name. [1]

Credit: From Guy Deutscher, Through the Language Glass: Why the world looks different in other languages (New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Co, 2010), by permission of the author.

It was these kinds of observations that originally got me hooked on translation. If speaking different languages gives you access to different perceptions of reality, then what’s the effect not only of switching continuously back and forth between languages but of pulling different segments of reality from one linguistic system and pushing them into another? That would be like taking your spaghetti strips and putting them back through the roller using a filter for bow tie pasta (farfalle, or butterflies, in Italian, by the way; so we can say with certainty that one woman’s bow tie is another woman’s butterfly, a great illustration of my point). The result, inevitably, would be a pasticcio (a hash, in both senses of the word: a pie and a patty, but also a mess; not to mention, of course, a pastiche).

Such an action is the classic attempt to put a square peg in a round hole, and that, most simply for me, describes the challenges and frustrations of translating in general. You know before you start that you will never produce an exact equivalent—something will get lost, something will get added, something will get distorted—but the act of trying illuminates the nature of a square peg, the nature of a round hole, and the nature of attempting to make them fit together.

Translating works of philosophy, to which I have devoted the last decade of my career, ups the ante even more, by taking the act to greater and greater levels of “meta” illumination; in the fashion of contemplating a glass bead game across a sort of three-dimensional chess board, in which systems of thought about the nature of reality and meaning are themselves put through the round hole of the pasta machine and made to adapt, willy-nilly. And this brings me to Barbara Carnevali’s magnificent book, Social Appearances.

The image of reality as a stuff that gets segmented according to culture suggests a semiotic structure based on a distinction between content (the dough) and form (spaghetti, ravioli, fettucini, cappellini…). Content would be the underlying substance that persists throughout change, while form would be the variable appearance that, in itself, is insubstantial. This, in a nutshell, describes the hierarchy in Western thought between the real and the illusory—Plato’s eternal ideals versus the ephemeral images that dance on the cave wall. From here, it takes little effort to stretch this vision into a normative view: that which is real (ideas) is worthy of study and admiration; that which is insubstantial (sensory perception, anything associated with the body and appearances), is unworthy of attention. One is high, the other is low; one is associated with masculine contemplation, the other with female vanity, and so on.

The way out of this unfruitful dichotomy—what Carnevali refers to as the Platonic-Christian impasse—lies through aesthetics. It’s not just about reversing the hierarchy, but about dispelling it altogether. If we can perceive the dignity in all that is sensual and sensory and transitory and insubstantial (an “atmosphere” or an “aura,” for instance, that feeling of a place that hits you like a brick when you walk into it), then we can also start to understand how social media, news commentators, celebrity gossip, all the flotsam and jetsam of the public space, made of nothing but images and opinions, has been able to highjack our imaginations and assume such vital and dangerous importance today . . . despite being nothing but frivolous and ridiculous.

It’s time for us to take appearances seriously. Carnevali’s proposal for a social aesthetics offers a model for understanding the modern world that has transformed my way of looking at reality and enriched it. What do Andy Warhol and Hannah Arendt have in common? The understanding that the public space made of images and impressions is where the real political battles are waged.

As Carnevali teaches us, it’s time we seek to understand the social dimension of prestige and display on its own terms: using the tools of the sister disciplines of aesthetics and economics.

Maybe it’s also time for me to throw out that pasta metaphor after all.

Zakiya Hanafi is the author of The Monster in the Machine: Magic, Medicine, and the Marvelous in the Time of the Scientific Revolution (Duke UP, 2000) and an Affiliate Assistant Professor of Human-Centered Design & Engineering at the University of Washington, Seattle. Barbara Carnevali’s Social Appearances for CUP is her eleventh book of philosophy in translation.